Planning vs. Doing: Reduce Attention-Switching Costs

At work, we often spend substantial time planning, only to struggle in the execution stage. You might lead an important project, build a thorough plan through multiple meetings, and prepare all the materials—then encounter unforeseen variables once execution begins and watch the plan slip. Even when you have listed your tasks, urgent issues and incoming requests can keep you from finishing on time. That happened yesterday; it will likely happen again today.

Narrowing the gap between planning and execution is critical to productivity. Investing heavily in planning without executing yields no outcomes. Focusing only on execution while neglecting planning leads to unclear goals and wasted effort. Daniel J. Levitin, author of The Organized Mind, offers a way to address this tension.

Planning and execution recruit different parts of the brain

Levitin emphasizes that in our information-rich world, it is important to separate planning from doing to reduce the brain’s load. The reason lies in how our brain is organized. Planning and doing are like a boss and a worker. To perform both well, we must form and maintain hierarchically organized multiple attentional sets and keep switching between them—from the boss who delegates, to the worker who does the job, back to the meticulous planner, and so on. Each of these switches is a shift of attentional set, and it incurs a cost similar to multitasking’s cost. The more these switches repeat, the more energy your brain consumes and the more productivity drops. To mitigate this, keep a stable attentional set for each stage and create an environment that supports that focus. Maintaining such an environment lowers the brain’s energy expenditure.

Levitin illustrates this structure with a car wash. Three distinct tasks are divided among three people. Because roles are separated, each person maintains a single attentional set and efficiency rises. This minimizes the metabolic cost that occurs when one person tries to perform multiple roles and repeatedly shifts attention.

One effective way to apply this is to distinguish the space for planning from the space for doing, while keeping them tightly linked.

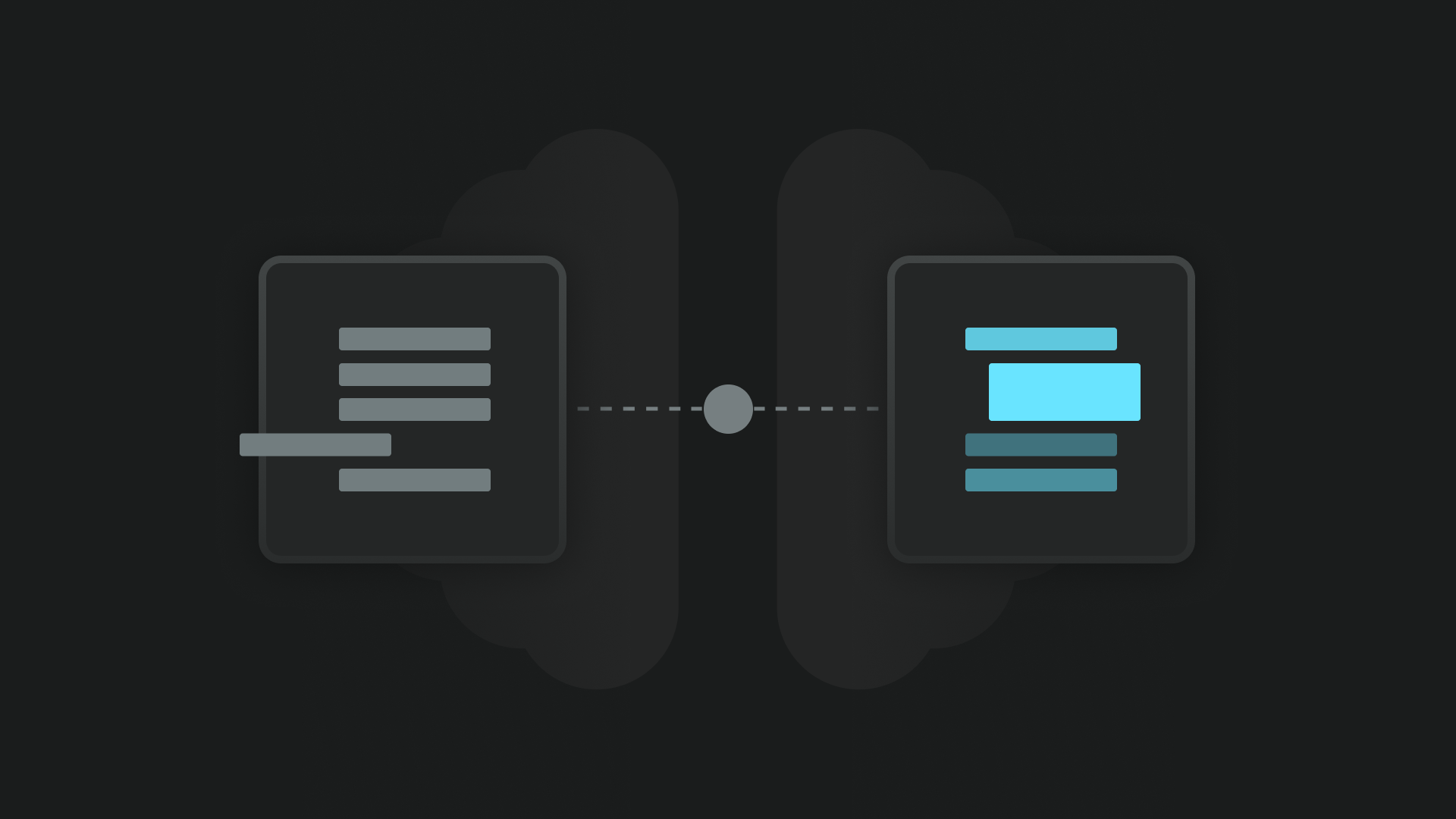

Prepare the work in your to do list; manage the execution of that work on your calendar. The to do list lets you enumerate what must be done. The calendar lets you place when it will be done and see it visually. The two systems complement each other and connect planning with execution.

This approach has clear advantages. By handling planning and execution in separate spaces, you can give fuller attention to the task at hand. By allocating time on the calendar, you make time decisions explicit and workable. And because you capture tasks in a list and then move them into scheduled blocks in the same overall workflow, you reduce the energy lost to switching attentional sets.

In short, separate the spaces for planning and doing, then connect them well.

The more distinct the spaces, the easier it is to sustain focus at each stage. The more coherently they interlock, the lower the switching cost. As Daniel J. Levitin argues in The Organized Mind, separating planning and execution so you can concentrate on each maximizes productivity in complex work. You spend less energy on needless switching and more on what matters.